Good practice note: Addressing contract cheating to safeguard academic integrity

Documents

Good practice note: Addressing contract cheating to safeguard academic integrity – October 2017

With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, TEQSA’s logo, any material protected by a trade mark, material sourced from third parties and where otherwise noted, all material presented in this document is provided under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence.

Information about the use of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms. Enquiries about the use of material protected by a trade mark or which has been sourced from a third party should be directed to the source of the relevant material.

The document must be attributed: Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency, Good Practice Note: Addressing contract cheating to safeguard academic integrity – October 2017.

Contacts

More information about the Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency, including electronic versions of this report, is available at teqsa.gov.au

Comments and enquiries about this report may be directed to:

Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency

Level 14/530 Collins Street MELBOURNE VIC 3001

T: 1300 739 585

F: 1300 739 586

E: comms@teqsa.gov.au

Provider resources

TEQSA’s role is to safeguard the interests of all students, current and future, studying within Australia’s higher education system. We do this by regulating and assuring the quality of Australia’s higher education providers.

In carrying out this work, we produce a number of resources aimed at supporting higher education providers understand their responsibilities under the Higher Education Standards Framework (Threshold Standards) 2015 (HES Framework).

HES Framework

The HES Framework is a legislative instrument that is structured to align with the student experience or ‘student life cycle’. It sets out the requirements for provider entry to, and continued operations within, Australia’s higher education sector. The Standards for Higher Education within the HES Framework apply to all providers offering courses leading to a regulated higher education award, irrespective of where and how a course is delivered. All providers are required to demonstrate their adherence to the HES Framework.

Guidance notes

Guidance notes are intended to provide advice and greater clarity when interpreting and applying selected areas of the HES Framework. They are not intended to be ‘how to’ documents, instead they outline what TEQSA will typically expect to see when assessing providers’ compliance.

Good practice notes

Good practice notes offer practical advice and examples of good practice to guide operations in regard to specific, higher education issues. The best practice guides are intended to support and promote the quality assurance approaches of providers.

More information and guidance on the HES Framework and our regulatory approach can be found at teqsa.gov.au

Author’s note

It has been my great pleasure to collaborate with TEQSA in writing this Good Practice Note. Addressing contract cheating to safeguard academic integrity incorporates much of my thinking and research on academic integrity since 2002, and focusses that knowledge on a new and emerging threat to higher education across the globe.

As the literature review in this document demonstrates, academic integrity is not a new field of inquiry, and I pay homage to the many researchers who have paved the way, over many decades. In addition, I wish to extend my thanks and appreciation to the many colleagues who contributed to this Note, both directly and indirectly. A special thank you to the Australian higher education providers who agreed to have their exemplary work showcased, so that other institutions could benefit from their good practice: Griffith University, the University of Western Australia, Deakin University, Curtin University, UniSA College and CQ University. Thanks also to my generous colleagues, both in Australia and abroad, who provided case studies of an academic integrity innovation that had been successful in their own contexts: Sonia Saddiqui, Wendy Sutherland-Smith, Gavin Hodgkinson, Michael Baird, Joseph Clare, Shiva Sivasubramaniam, Ann Rogerson, Salim Razi and Greg Preston. Other colleagues provided valuable insights or pointed me in the right direction regarding resources: Jon Yorke, Sharon King, Jenny Roberts and Michael Draper.

An enormous debt of gratitude is owed to my many research partners on numerous Australian Office for Learning and Teaching funded projects, without whose inspiration, expertise and perseverance, the research on academic integrity would be significantly less advanced: Saadia Mahmud, Julianne East, Margaret Green, Colin James, Ursula McGowan, Lee Partridge, Ruth Walker, Margaret Wallace, Karen van Haeringen, Lee Pointon, Rowena Harper, Sonia Saddiqui, Cath Ellis, Phil Newton, Pearl Rozenberg and Michael Burton. I also wish to acknowledge the leadership of two key organisations in addressing contract cheating: the Quality Assurance Agency (UK) and the International Center for Academic Integrity (USA). Finally, I am grateful every day to work for the University of South Australia, where my long-standing interest in academic integrity, and my desire to effect lasting cultural change for students and staff, continues to be supported.

This Good Practice Note does not purport to deliver a ‘solution’ to the problem of contract cheating, but aims to provide a stimulus for reflection and a call to action, both in our own institutions, and as part of a sector-wide collaboration.

Tracey Bretag

Associate Professor (Higher Education)

Director, Office for Academic Integrity, UniSA Business School

Foreword

TEQSA’s purpose is to safeguard student interests and the reputation of Australia’s higher education sector. We do this by assuring the quality of higher education through a proportionate, risk-reflective approach to regulation. This approach encourages diversity, innovation and excellence while allowing providers to pursue their individual missions. Our work as an external quality assurer is underpinned by the intention of encouraging, supporting and recognising effective internal quality assurance practices. This good practice note, the first in a new series of resources produced by TEQSA, aims to support and promote the quality assurance approaches of providers in relation to academic integrity.

TEQSA has identified academic integrity as a key issue in our Corporate Plan for 2017-21. We recognise that breaches of academic integrity have broad implications; in addition to the risks to the reputation to Australian higher education, there are also implications for individual providers in relation to progression and attrition rates. Academic integrity also poses risks for employers, student mobility and of course the integrity of certification.

Concerns regarding academic integrity have been widely reported, with contract cheating taking prominence. In November 2014, TEQSA wrote to all higher education providers alerting them of the risk to academic integrity posed by the contract cheating website, MyMaster. Providers were asked to report on action taken to address the purchase of assignments by students through services such as MyMaster. TEQSA reported on provider’s initial responses in early 2015, while some providers undertook more extensive investigations and other measures before submitting further information. In 2016, TEQSA engaged Associate Professor Tracey Bretag to review this further information in the light of the 2015 Higher Education Standards Framework, where it was found that compliance was achieved to varying degrees. The review also identified good practices and areas for development. In response, TEQSA moved to include standards relating to academic integrity into the core set of standards used to assess applications from all providers and committed to the development of further support resources.

During 2017, preliminary findings of the Office of Learning and Teaching Strategic Priority Project ‘Contract Cheating and Assessment Design: Exploring the Connection’, where over 15, 000 students were surveyed from eight Australian universities and four non-university providers including pathway providers, found that students who speak a language other than English at home, those who are dissatisfied with the teaching and learning environment, and those who perceive that ‘there are lots of opportunities to cheat’ are the most at risk of engaging in contract cheating. Studies also suggest students at pathway providers appear to be more at risk of some cheating behaviours than students in higher education providers. This suggests that the risks to academic integrity should be addressed from the initial introduction to higher education, to ensure integrity of admission processes and to mitigate the potential impact on attrition rates. Research has found that discussion regarding academic integrity, and particularly contract cheating, in the sector is not yet well advanced but that good work is being done.

In addition to releasing a revised guidance note on academic integrity in August 2016 to support the requirements of the Higher Education Standards Framework 2015, we are keen to see increased engagement between providers and students to address the risks that contract cheating poses to the integrity of the sector. This good practice note provides practical advice and examples of good practices to facilitate that engagement.

Anthony McClaran

Chief Executive Officer

Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency

Purpose

This Good Practice Note is intended to complement the Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency (TEQSA) Guidance Note: Academic Integrity.

The recommendations in this Good Practice Note correspond to the Higher Education Standards Framework (Threshold Standards) 2015 (HES Framework) and provide specific, practical advice to address contract cheating in relation to five critical areas:

- policies to promote academic integrity

- policies and procedures to address academic integrity breaches

- actions to mitigate risks to academic integrity

- the provision of academic integrity guidance, and

- good practices to maintain academic integrity.

This Good Practice Note provides Australian higher education providers with access to research and exemplars to enable the development of policies and processes to minimise contract cheating. This endeavour is part of a sector-wide agenda to safeguard academic integrity and is critical to protect students’ learning outcomes, institutional reputations, educational standards, professional practice and public safety.

Background

Since around 2000, numerous media reports have highlighted the importance of academic integrity to the Australian higher education sector. In the early years, the focus was on plagiarism and the impact of increasing internationalisation on academic standards (see Bretag, 2016). As a result, considerable research has been conducted; much of it funded by the Australian Office for Learning and Teaching[1], on how best to address plagiarism, support international students, and ensure that all students receive adequate academic literacies training. By and large, the emphasis has been on developing and promoting clear academic integrity policy and processes for undergraduate students, coupled with appropriate support services and resources. Various research projects and investigations demonstrated that all Australian universities had appropriate policies in place (Grigg, 2009), and generally speaking, there had been a shift in emphasis from a punitive to educative approach in relation to academic integrity (Bretag et al., 2011).

In late 2014, the focus shifted again. A high impact media story relating to the ‘MyMaster scandal’ – where the Fairfax media exposed widespread use by students of the commercial cheat site ‘MyMaster’ – led to Australian higher education providers beginning to address this new threat to academic integrity known as ‘contract cheating’. This occurs when students outsource their assessments to a third party, whether that is a commercial provider, current or former student, family member or acquaintance. It includes the unauthorised use of file-sharing sites, as well as organising another person to take an examination.

During this period, higher education providers around the world (for example, in the United States, Canada, South America, United Kingdom and Europe) were experiencing similar concerns with the proliferation of unscrupulous and marketing- savvy commercial organisations providing bespoke essays for students. The Australian higher education regulator, TEQSA, requested the 17 higher education providers named in relation to the MyMaster incident to provide an ‘assurance of academic integrity’ and specifically demonstrate how the threat of contract cheating was being addressed.

Based on the higher education providers’ responses, TEQSA prepared the Report on student academic integrity and allegations of contract cheating[2] in 2015. In 2016, further analysis was conducted of additional information provided by the 17 higher education providers named in the media, as well as documents provided by 13 other higher education providers, against Part A of the HES Framework, to assess how effectively the higher education providers had responded to the allegations that contract cheating had occurred in their institutions. The analysis concluded that the 17 higher education providers identified as being implicated in the MyMaster incident had provided responses which complied with the HES Framework, to varying degrees. Three providers were noted as exhibiting excellent academic integrity practice: Griffith University, the University of Newcastle and CQUniversity. Six key areas were identified as requiring additional attention across the sector:

- the need for higher education providers to take a holistic approach to academic integrity

- the value of consistent academic integrity education for both staff and students

- the importance of innovative assessment design which goes beyond invigilated examinations

- the requirement for text-matching software to be used consistently for both education and detection

- the necessity of training and professional development for academic integrity decision-makers, and

- the role of academic integrity breach data for quality assurance and improvement.

Literature review [3]

How prevalent is cheating?

Most of the highly cited work on academic integrity around the world has been based on large surveys, which have asked students to self-report their cheating behaviours (see Table 1). None of these surveys have contradicted earlier work by Bowers (1967) or McCabe and colleagues (1992, 1994, 1995, 1997, 1998, 2005), in that a large proportion of students in every survey report engaging in one or more ‘questionable’ behaviours (such as copying or using unauthorised notes in an exam). However, the percentage of self-reported cheating does vary, from 46% (Smyth & Davis, 2004) to 67% (McCabe, 1992) and 72% (Brimble & Stevenson-Clarke, 2005), depending on how ‘cheating’ is defined in the research. Table 1 provides an overview of some of the main student surveys conducted around the world.

Table 1: Student surveys of self-reported cheating

|

Year |

Authors |

Location |

Number of respondents |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2005 |

Brimble and Stevenson-Clarke |

Australia |

1084 |

|

2005 |

Marsden, Carroll, and Neill |

Australia |

954 |

|

2006 |

De Lambert, Ellen, and Taylor |

New Zealand |

1126 |

|

2007 |

Lin and Wen |

Taiwan |

2068 |

|

2008 |

Kidwell and Kent |

Australia |

459 |

|

2010 |

Teixeira and Rocha |

Portugal |

2675 |

|

2010 |

Stephens, Romakin & Yukhymenko |

Ukraine |

378 |

Source: Bretag et al 2014, p. 1152

While the proportion of students who admit to some form of academic integrity breach is generally high, the percentage of students who report having plagiarised varies from as low as 19% (Scanlon & Neuman, 2002), to 26% (Ellery, 2008), 66% (Franklyn-Stokes & Newstead, 1995) and 81% (Marsden, Carroll & Neill, 2005). Self-reported rates of plagiarism in postgraduate work also vary widely from 5% (Segal et al., 2010) to 27% (McCullogh & Holmburg, 2005) and 42.6% (Gilmore et al., 2010). The percentage of students who report engaging in contract cheating is comparatively low, ranging from 3.5% to 7.9% (Curtis & Clare, 2017). Preliminary findings from the Contract Cheating and Assessment Design (CCAD) Project indicate that 6% of Australian students have engaged in one or more contract cheating behaviours (Bretag & Harper et al., 2017) and recent research in the Czech Republic found that 8% of students admitted to contract cheating (Kralikova, 2017).

Who cheats?

Numerous studies have demonstrated the influence of demographic or other contextual variables on cheating behaviour, including:

- gender

- age

- discipline of study

- learning orientation

- linguistic background, and

- use of technology.

The literature demonstrates that males self-report more cheating than females (Crown & Spiller, 1998; Marsden et al., 2005; Kremmer et al., 2007; Bretag & Harper et al., 2017). Younger students are more likely to cheat than older students (Brimble, 2016; Marsden et al., 2005), and younger students tend to engage in more ‘collaborative cheating’ than their older peers (Kremmer, Brimble & Stevenson-Clarke, 2007; Bretag & Harper et al., 2017).

McCabe and Trevino (1993) reported differences in dishonest behaviours among students according to discipline, noting that business students self-report the most cheating, followed in order by engineering, science, and the humanities. The likelihood of business students cheating more than non-business students has been supported by other studies (McCabe & Trevino, 1995; Smyth & Davis, 2004). Marsden et al. (2005) found that engineering students were more likely to cheat than students from all the other disciplines in the study, a finding supported by recent research by Bretag and Harper et al. (2017).

Some studies have found that students with a lower Grade Point Average cheat more (Crown & Spiller 1998; McCabe & Trevino 1997). Marsden et al. (2005) also reported that ‘less learning orientation and more goal orientation were associated with higher rates of cheating’ (2005, p. 7).

Students for whom English is an Additional Language (EAL) have unique challenges in meeting the requirements of English-based instruction. Numerous studies have highlighted that plagiarism is a particular concern for EAL students (Marshall & Garry, 2006; Pecorari, 2003; Vieyra, Strickland & Timmerman, 2013). Bretag et al. (2014) found that international students were more than twice as likely as Australian domestic students to convey a lack of confidence in how to avoid an academic integrity breach and twice as likely to have been reported for a breach. Recent research on contract cheating by Bretag and Harper et al. (2017) found that EAL students were significantly over-represented in the cheating group.

Numerous commentators have addressed the specific role played by the Internet in relation to writing practices, particularly plagiarism (see for example, Lathrop & Foss, 2000; Howard, 2007; Park, 2003; Sutherland-Smith, 2008; 2016). Scanlon and Neumann (2002, p. 380) reported that a small percentage of students admitted to:

- copying an entire paper from the Internet (5.4% sometimes, 3.2% often or very frequently)

- requesting a paper to submit for grading (8.3% sometimes, 2.1% often or very frequently), and

- purchasing a paper from an essay mill (6.3% sometimes, 2.8% often or very frequently).

Why do students cheat?

A number of writers (Blum, 2016; Bretag, 2007, 2013; Foster, 2016; Heuser, Martindale & Lazo, 2016; Kezar & Bernstein-Sierra, 2016) have situated academic misconduct in the context of an increasingly commercialised, internationalised and highly competitive higher education sector. The shifting emphasis from tertiary education as a transformative learning experience to one that focusses on credentials for employment has also had an impact on the values and practices of academic integrity.

Research has consistently shown that one of the strongest motivators of students’ cheating behaviour is peer influence (McCabe & Trevino, 1993, 1997; Rettinger & Kramer, 2009). In addition, the ‘likelihood of being caught and the severity of the consequences’ is a powerful deterrent to cheating behaviour. In numerous studies (Ahmad et al., 2008; Diekhoff et al., 1999; Power, 2009) students have reported that their fear of being caught combined with their concerns about the potential punishment was the main reason for not engaging in unethical conduct, rather than their intrinsic motivation to learn with integrity.

Lack of understanding also has an important part to play. Gullifer and Tyson (2014) found that only half of the students in their study had read the university’s plagiarism policy and confusion remained about the meaning and behaviours associated with plagiarism. Other studies have also reported that both students and staff struggle to understand and agree on the meanings and practices of academic integrity (Foltynek et al., 2014; Glendinning, 2014; 2016).

Blum (2016) lists the characteristics of contemporary higher education students which impact on their motivations to follow the principles of academic integrity. These include:

- differing motivations for enrolling in higher education

- divergent understandings about authorship practices and norms of sharing

- pressures to achieve

- lack of interest in learning content

- complex lives

- time pressures

- developmental issues, and

- mental health.

The widely cited article by Park (2003) lists nine motives for student plagiarism, many of which overlap with Blum (2016). These include:

- genuine misunderstanding

- ‘efficiency gain’ (a high grade for the least effort)

- time management

- personal values or attitudes

- defiance

- students’ attitudes to teachers and class

- denial or neutralisation

- temptation or opportunity, and

- lack of deterrence.

Contract cheating

The term ‘contract cheating’ was first coined by Clarke and Lancaster (2006). As noted earlier, contract cheating occurs when students employ or use a third party to undertake their assessed work for them and these third parties may include:

- essay writing services

- friends, family or other students

- private tutors

- copyediting services

- agency websites, or

- ‘reverse classifieds’ (Lancaster & Clarke, 2016, p. 639).

While clearly not a ‘new’ phenomenon, most commentators maintain that there has been a global rise in contract cheating in recent years, across all disciplines. This has raised the level of community concern about the credibility of higher education qualifications and academic outputs, and correspondingly seen a rise in the number of media stories highlighting the issue, such as the 2015 MyMaster incident.

Of particular concern is the proliferation of marketing-savvy commercial providers who bombard students via social media, online platforms and other advertising forums of cheating services about their ‘academic services’. Newton and Lang (2016) identified five categories of third-party commercial providers:

- academic custom writing

- online labour markets

- pre-written essay banks

- file sharing sites, and

- paid exam takers.

For a price, and even within extremely short turnaround timelines of hours rather than days, any assessment item can be contracted out to a third party (Newton & Lang, 2016). Employment portfolios, reflective journals, case studies, experiential reflections, online presentations, group projects, research proposals, and even complete doctoral dissertations can all be bought like any other commodity. While there is no type of assessment which will prevent outsourcing, recent research has demonstrated that some assessment tasks are less likely to be outsourced (Bretag & Harper et al., 2017).

Educators and researchers agree that contract cheating is qualitatively different to plagiarism, collusion, or the other breaches which have been the subject of attention in recent years, and so requires an entirely different approach. Walker and Townley (2012) point out that cheating that involves third parties is difficult to detect[4] and constitutes a form of fraud. Moreover, while educational responses have evolved to address longstanding issues of plagiarism, lack of understanding and/or poor academic literacies, education alone is not sufficient to address such a deliberate form of cheating (Bretag & Harper et al., 2016).

However, students and teachers seem not to share the same concern about this issue (Bretag & Harper et al., 2017). Most educators consider strict penalties such as suspension or expulsion to be appropriate outcomes when contract cheating is detected, whereas students tend to take a much more lenient view, regarding failure in the assessment task to be a sufficient response (Newton, 2015). While research in the UK by Rigby et al. (2015) found that 50% of their student respondents (n=90) said that they would be willing to purchase an assignment, recent empirical work by the Contract Cheating and Assessment Design Project (Bretag & Harper et al. 2017) found that only 6% of students (n=15,047) reported engaging in one or more of five contract cheating behaviours.

Bertram Gallant, an advocate for ‘ethical classroom environments, good pedagogy, and well-designed assessment’ to prevent cheating (2008) now argues for a strong moral response which makes clear that ‘contract cheating’ is not the same as the less sinister and more widely accepted practice of ‘ghostwriting’ (Bertram Gallant 2016). Contract cheating has ramifications for individuals’ learning outcomes, institutional reputations, educational standards and credibility, professional practice, and public safety, particularly if it is somehow normalised as an acceptable way for academic work to be accomplished.

What can be done?

The view that teaching staff have a pivotal role to play in terms of their influence on students’ behaviour has been the subject of much commentary and recommendations for good practice (Bertram Gallant, 2008; Carroll, 2002; HEA, 2011a, 2011b; Lang, 2013), particularly in relation to curriculum and assessment design. While the phrase ‘designing out’ student cheating (HEA, 2011b) has been commonly used, there is now less confidence that assessment – even that which is ‘original, sequential, reflective and personalised’ (Bretag & Harper et al., 2016) – is sufficient to address some forms of academic misconduct such as contract cheating.

In the current resource-constrained working environment which characterises higher education, academics may not have adequate time or support to demonstrate best practice. Teaching materials may be repurposed versions of others’ work, poorly referenced, if at all. Assessment tasks may remain unchanged from (ever shortening) study period to study period, with creativity and innovation in assessment little more than an unfulfilled aspiration. Feedback to students might be minimal and face-to-face contact almost non-existent.

Rather than focusing solely on the responsibilities of individuals (whether those individuals are students or teachers), establishing a culture of integrity requires a holistic and multi-stakeholder approach which promotes integrity in every aspect of the academic enterprise (Bretag, 2013). This includes:

- higher education provider mission statements and marketing

- admissions processes

- nuanced and carefully articulated policy (with the resources to promote the policy and the ‘teeth’ to enact it)

- assessment practices, and

- curriculum design.

Students need to be provided with information during orientation, with embedded and targeted support in courses and at every stage, and frequent and visual reminders on campus. A holistic culture will require:

- partnering with students

- professional development for staff

- research training, and

- the use of new technologies to assist scholars at all stages of study and research to avoid integrity breaches, and as a tool to detect and respond appropriately to breaches when they occur (Bretag, 2013).

In the UK and Australia, such a holistic approach takes as its starting point policies that include education about academic integrity for both teachers and students, plus real consequences for breaches (often referred to as ‘penalties’ in the UK and Australia, or ‘sanctions’ in the US).

The following sections provide practical recommendations for good practice in promoting academic integrity generally and addressing contract cheating specifically, taking the HES Framework as a starting point.

1. Policies to promote academic integrity

The Academic Integrity Standards Project[5] (Bretag et al., 2011) identified ‘five core elements’ of exemplary academic integrity policy.

These include: access, approach, responsibility, detail and support, as briefly summarised below in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Five core elements of exemplary academic integrity policy

Source: Academic Integrity Standards Project

- Access: The policy is easy to locate and read, and is concise and comprehensible.

- Approach: There is a statement of purpose with an educative focus up-front and throughout the policy.

- Responsibility: The policy details responsibilities for all stakeholders, including students, teachers, professional staff and senior managers.

- Detail: The policy provides extensive but not excessive description of breaches, outcomes and processes.

- Support: The policy points to proactive and embedded systems to enable implementation of the policy

Good practice example 1: Clearly define contract cheating in academic integrity policy

In relation to contract cheating, an exemplary academic integrity policy needs to include clear information which:

- defines and describes contract cheating

- provides information for both staff and students about why contract cheating is considered to be such a serious breach, how it undermines the values of the

- academic community, and impacts on the value of degrees and the reputation of the higher education provider

- includes clear details about how to identify and respond to instances of contract cheating, and

- educates both staff and students about resources to support learning regarding the outsourcing of assignments.

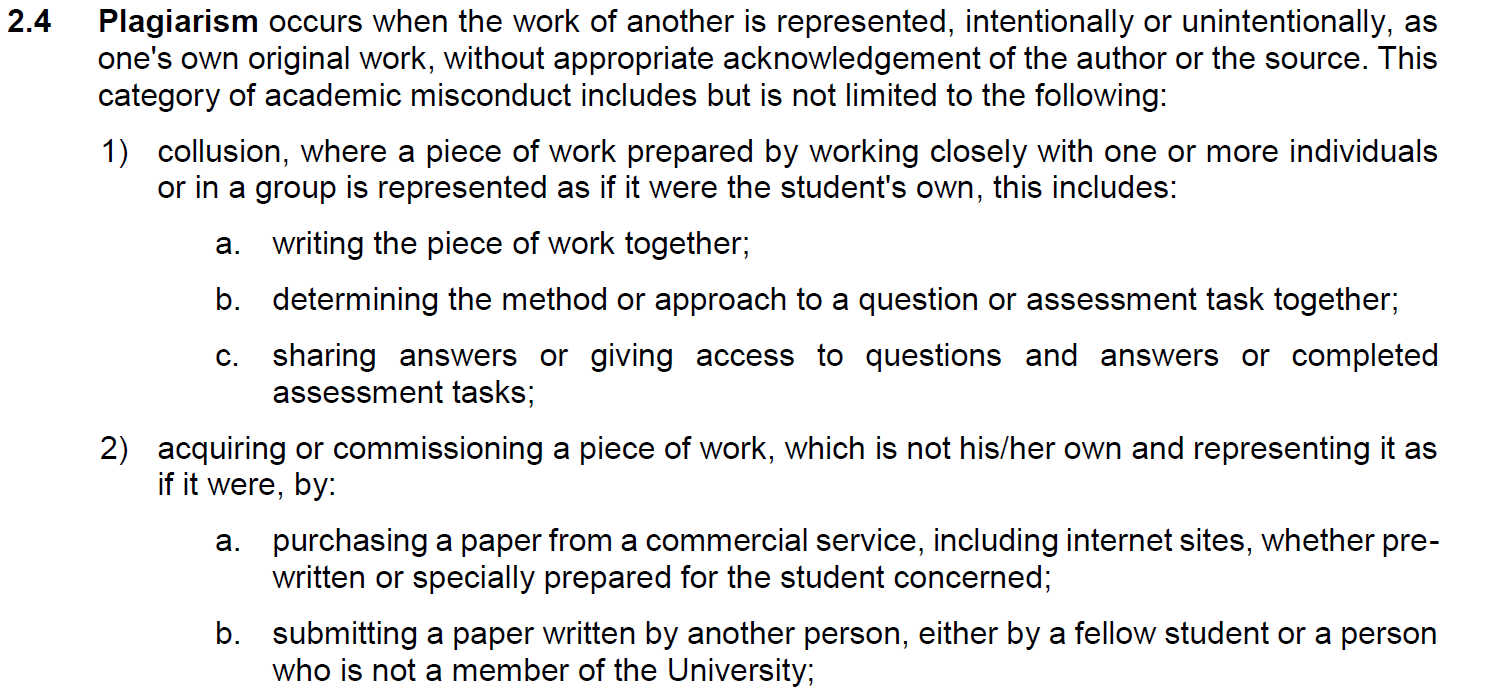

Importantly, a good policy will indicate the likely outcome or penalty for contract cheating so that this issue is dealt with consistently across the higher education provider. Griffith University’s academic integrity policy and processes are exemplary in this regard, as in the example shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Excerpt from Griffith University Academic Integrity Policy

Source: Excerpt from Griffith University’s Institutional Framework for Promoting Academic Integrity among Students, which clearly defines outsourcing of assessment as a form of plagiarism - policies.griffith.edu.au

Good practice example 2: Include information about academic integrity and contract cheating in online platforms, course outlines and mandatory courses

Research has demonstrated that many students (and staff) are confused about academic integrity requirements at their institution. Given that contract cheating is a relatively new phenomenon, it is imperative that higher education providers include specific information about this in multiple forums, such as learning management systems and course outlines. Internationally recognised best practice is to mandate that students complete an academic integrity training module early in their programs. Comparable training should also be provided to staff. The highly acclaimed Academic Conduct Essentials program at the University of Western Australia (see Figure 3 below) is one such compulsory program for students.

Figure 3: Excerpt from University of Western Australia website

Source: www.student.uwa.edu.au/learning/resources/ace

Good practice example 3: Visual reminders that contract cheating is not acceptable

Frequent and visual reminders regarding academic integrity generally, and contract cheating specifically, are part of a holistic approach to promote integrity on campus. A number of higher education providers conduct ‘marketing campaigns’, particularly at strategic times during the semester (such as Orientation and just before exams) that include distributing leaflets around campus, and posters and large adhesive decals in strategic locations. Deakin University[6] has recently worked closely with students to develop a campaign which raises awareness about contract cheating (see Figure 4 below).

Figure 4: Deakin University Contract Cheating Awareness Week Campaign

Source: ‘Know it’s cheating’, Contract cheating campaign developed by students at Deakin University

Making visible that ‘contract cheating is not acceptable’ requires the message to be reiterated in both face-to-face and online environments. It is a relatively simple matter to block students’ access to known commercial cheat sites while on campus, and simultaneously provide a counter-message about academic integrity. Whether a student deliberately or inadvertently tries to access such a site, they should receive a message such as: ‘This site has been blocked because it is not a legitimate learning service’, along with a link the higher education provider’s academic integrity resources.

Good practice example 4: Student-led, engaging activities to promote a culture of integrity

Both staff and students need to be reminded about the pitfalls of contract cheating in ways that go beyond mere communication of policy. Engaging activities that work in tandem with other campus events (Saddiqui, 2016) are the most effective in terms of reaching a wide audience. Encourage students to lead interactive activities that focus on integrity at Orientation, Open Day, Careers Day, etc. Ideas for activities include interactive games (e.g. giant jenga, tug-of-war, juggling, hoola-hooping, treasure hunts). Some higher education providers hold specific events or whole weeks dedicated to academic integrity. Another useful approach is to encourage students to participate in sector-wide activities such as the annual ‘International Day of Action Against Contract Cheating’.

Figure 5: Image from International Day of Action Against Contract Cheating website

Source: Original image by Inkan Hertanto, University of California (San Diego) student, used to promote International Day of Action Against Contract Cheating

2. Policies and procedures to address academic integrity breaches

Contract cheating is a particular and egregious academic integrity breach which is qualitatively different to other breaches (such as minor or unintentional plagiarism).

The Centre for Studies in Higher Education (2002) describes the complete outsourcing of an assignment (contract cheating) as being at the extreme end of the plagiarism continuum, and therefore requiring a much more significant ‘penalty’ than breaches at the other end of the continuum such as inadvertent or minor plagiarism.

Good practice example 5: Include information about contract cheating in academic integrity policy

The best examples of academic integrity policy in Australian higher education providers recognise that not all academic integrity breaches are the same, and therefore not all breaches will result in the same outcomes or penalties. In response to recent concerns about contract cheating, many Australian higher education providers have updated their academic integrity policies to include specific guidance on the identification of, and likely outcome or penalty for, contract cheating (see Good practice example 1 above).

Good practice example 6: Use data to identify contract cheating ‘hot spots’

All higher education providers collect and maintain data for the purpose of quality assurance and improvement. Much of this data could be used to identify contract cheating ‘hot spots’. For example, academic integrity breach data should be maintained in a central, confidential database and regularly analysed to determine where contract cheating is occurring (faculties, courses, types of assessments) so that resources can be allocated in areas most prone to contract cheating. Other data sources include feedback from:

- academic integrity decision-makers

- appeals committees

- senior managers

- teaching staff

- students, and

- policy-makers in other functional areas (see Bretag & Mahmud, 2016).

Good practice example 7: Create a simple process for referring contract cheating cases

Identifying contract cheating is only the first step. Teaching staff need to be aware of the seriousness of contract cheating and understand the importance of referring such cases for formal investigation, rather than ‘dealing with it themselves’. Teaching staff therefore need to be familiar with their higher education provider’s procedures for referring contract cheating cases for further investigation and follow-up. Simple flowcharts and guidelines should be communicated to teaching staff at regular intervals, via both electronic and hard copy means. Staff should be made aware that where there is evidence of a student having outsourced their work, this should always be forwarded to an appropriate decision-maker for further investigation. The best flowcharts are simple, easy to communicate (and remember), and available online, as in the example from Curtin University in Figure 6 below.

Figure 6: How to manage plagiarism resource, Curtin University

Source: Excerpt from Academic integrity at Curtin University: Staff guidelines for dealing with student plagiarism 2015

Good practice example 8: Implement appropriate and consistent responses to contract cheating

Ensure that serious breaches such as contract cheating are dealt with consistently and fairly. It would not be reasonable for contract cheating, with the likelihood of a serious penalty such as suspension or expulsion, to be determined by an individual academic or single decision-maker. Establish formal procedures for a committee which includes representation from both staff and students to investigate and decide outcomes. Ensure that members of this decision-making body are well-trained, and that the procedures are fully documented and shared across the whole higher education provider. Conduct regular audits to ensure that all faculties are following the same process and applying the same outcomes for contract cheating (see Figure 7 below).

Figure 7: Guidelines for Applying Penalties, Curtin University

Source: Excerpt from Academic integrity at Curtin University: Staff guidelines for dealing with student plagiarism 2015

Good practice example 9: Communicate outcomes for contract cheating to staff and students

Both staff and students should feel confident that contract cheating is being dealt with fairly and consistently. Recent data from the CCAD Project (Bretag & Harper et al., 2017) found that 33% of staff who had referred serious cheating cases for investigation were not informed of the outcomes of the process. This has the potential to impact on teachers’ confidence levels about the process, as well as make it less likely that cases will be referred in the future. A simple solution is to inform all relevant staff members of the outcomes, whether in hard copy or via email. In addition, the higher education provider should publish de-identified data on the institution’s intranet, available to both staff and students, which details at the very least the types of breaches being investigated in a given period, along with the associated outcomes. A brief, regular ‘Academic Integrity’ newsletter with this information could also be distributed via staff and student portals. Griffith University is exemplary in this regard (see Figure 8).

Figure 8: Excerpt from Griffith University website – Academic Integrity Data

Source: Screen shot from Griffith University’s academic integrity website which transparently reports academic integrity breaches to the academic and broader community.

Good practice example 10: Provide training on how to identify contract cheating

Both teaching staff and academic integrity decision-makers require professional development in how to identify contract cheating. Unlike textual plagiarism which is generally able to be identified through text-matching software and/or the teacher’s knowledge of the source content, contract cheating by its very nature is difficult to identify. Bespoke essays written by a commercial provider or acquaintance, depending on the quality, will not result in a high ‘Similarity Score’. In fact, a low text-matching score may be a trigger for further investigation. Simple marking guidelines, instructions, and reminders should regularly be communicated to those who need to identify contract cheating, particularly markers and academic integrity decision-makers. Online resources and face-to-face workshops are also useful, particularly around key assessment points and marking times. The University of Wollongong provides training for markers to assist in the identification of contract cheating, as in the following excerpt from a presentation by Dr Ann Rogerson in Figure 9.

Figure 9: Excerpt from presentation by Dr Ann Rogerson

3. Actions to mitigate risks to academic integrity

Actions to mitigate risks in relation to contract cheating should include a range of preventative measures that take into account the student life-cycle from (pre)admission through to graduation.

Good practice example 11: Provide training for all staff

Students, teachers and academic integrity decision-makers are not the only stakeholders of academic integrity. Librarians, academic developers, learning advisors, counsellors and other support staff all need to be informed about contract cheating. Higher education providers should consider inviting academic support staff to professional development workshops for teachers, or offering separate workshops that meet the specific needs of those staff members. For example: professional staff who deal with admissions, pastoral care and referral to support services or assist with input of grades, compilation of Turnitin reports (at higher education providers where this is the process), examination invigilation, course homepages and unit outlines, to mention just a few examples.

Other non-student focussed professional staff also need appropriate induction, training and ongoing support. For example, facilities management staff are critical stakeholders as these colleagues are usually the first to see (and have the opportunity to remove) contract cheating advertising. Professional staff are too often ‘left out of the loop’ regarding contract cheating, and need advice and support about how their specific roles can contribute to fostering a culture of integrity to counter contract cheating.

Figure 10: Examples of cheatsite advertising

Source: Tracey Bretag (facilities staff have a ‘frontline’ role in removing cheat site advertising)

Good practice example 12: Establish an office responsible for promoting academic integrity and responding to breaches

As early as 2011, the Higher Education Academy (UK) (2011a; 2011b) recommended that higher education providers should have in place a standing committee with a specific academic integrity remit. More recently, a number of Australian higher education providers have recognised the critical importance of academic integrity and the corresponding need to resource this operational area. As part of the response to contract cheating incidents in late 2014/early 2015, The University of Sydney established the Office for Educational Integrity and the University of South Australia established the Office for Academic Integrity in the UniSA Business School[7]. Such an office can provide the academic community with a central point of expertise for all matters relating to the promotion of academic integrity, as well as the ability for higher education providers to respond in a timely manner to specific threats such as contract cheating.

Good practice example 13: Inform all stakeholders about contract cheating

The specific issue of contract cheating needs to be communicated to all stakeholders, including:

- those responsible for recruitment and admissions

- the CEO/Vice-Chancellor

- senior managers

- governing bodies, and

- learning and teaching committees to mention just a few.

Similarly, the issue needs to be discussed with students at all levels of their candidature, beginning with offer of enrolment through to orientation, and at key points during the student’s program (including Higher Degree by Research students). Reminders about the potential consequences of contract cheating are best communicated to students in relation to assessment, and well in advance of assignment due dates.

Good practice example 14: Share breach data with senior managers and decision-makers

Many higher education providers provide detailed academic integrity breach data to the Academic Board, the CEO/Vice Chancellor, Corporate Governing Body, Teaching and Learning Committees and other critical stakeholders such as Heads of Schools. This ensures that academic integrity remains at the forefront of key decision-makers’ agendas, and also provides opportunities for discussion and action regarding emerging threats to academic integrity such as contract cheating.

Good practice example 15: Provide consistent messages about academic integrity at all points of study

Many higher education providers provide a pathway to university study and as such play a crucial role in preparing students to meet expectations in relation to academic standards and integrity. It is particularly important that students undertaking foundation studies or other pre-university courses receive adequate training in the values and practices of academic integrity. Recent research by the CCAD Project (Bretag & Harper et al., 2017) found that students from Non-University Higher Education Providers (NUHEPs) reported similar rates to University students of obtaining an assignment with the intention of submitting it as their own, but were six times more likely to pay money for it. Educating NUHEP students about the pitfalls of contract cheating includes ensuring that this group of students have the necessary skills to complete their own work so that they are less likely to be influenced by advertising from commercial cheat sites. UniSA College details the specific skills such as referencing and how to write assignments that will be taught as part of the Foundation Studies Program (see Figure 11 below).

UniSA College also rigorously follows the University of South Australia’s Academic Integrity Policy, with trained Academic Integrity Officers providing guidance, mentoring and consistent outcomes to those students who breach the policy.

Figure 11: UniSA College Foundation Studies – excerpt from website

Source: Excerpt from UniSA College website

Good practice example 16: Support teaching staff to address contract cheating

The CCAD Project (Bretag & Harper et al., 2017) found that only 15.5% of teaching staff agreed that staff workload assisted in minimising contract cheating, while the majority (57.5%) ‘disagreed’ and ‘strongly disagreed’. Only 14.4% and 14.9% respectively agreed that performance management and recognition or reward supported their efforts to minimise contract cheating (Harper & Bretag et al. 2017, in progress).

It is therefore critical that higher education providers create an environment and practical support that make it both possible and probable that staff will both promote integrity and respond to breaches if and when they occur. Coordinators of large core courses are under particular pressure to manage assessment and moderation processes in a timely fashion, and may find the requirement to identify and respond to academic integrity breaches difficult without adequate workload and professional staff support. Teaching staff need practical resources that do not add an additional time burden, as in the following example in Figure 12 from Curtin University.

Figure 12: Curtin University, staff resources

Source: Advice and resources on contract cheating available to teaching staff at Curtin University

Teaching staff also need recognition of their efforts; for example, as part of the performance review process or other reward structures. The Office for Academic Integrity in the University of South Australia Business School recently established an ‘Academic Integrity Champion’ award based on three criteria:

- How has the staff member promoted academic integrity in their course or program?

- How has the staff member responded to academic integrity breaches?

- How has the staff member made academic integrity part of their portfolio of (teaching and learning) achievements?

While such an award will not ‘solve’ the problem of contract cheating, it does go some way to highlighting the importance of academic integrity and recognising the efforts of teaching (and professional) staff to address concerns in their own spheres of influence.

Good practice example 17: Use assessment design to make contract cheating ‘less likely’

Authentic, individualised and experiential assessment design has long been touted as the ‘solution’ to contract cheating. Recent research from the CCAD Project (Bretag & Harper et al., 2017) has challenged this myth. The data from the project indicated that no assessment types are immune to contract cheating, but student survey respondents also suggested that four types of assessment are ‘less likely’ to be outsourced. These include:

- reflections on practicums

- oral defences of written work (vivas)

- assignments that relate to students’ personal experience or which have been individualised, and

- supervised assessments which are completed in-class.

The data from the CCAD Project has provided an evidence base which demonstrates that assessment design alone is not the answer to contract cheating, but nevertheless plays an important role in addressing this threat to academic integrity[8] (see Bretag & Harper et al., 2017).

Figure 13: Four assignments ‘less likely to be outsourced’

Source: Bretag & Harper et al. (2017), Contract Cheating and Assessment Design Symposium Infographic

Good practice example 18: Use text-matching software for both detection and education

Text-matching software such as Turnitin or Urkund is used by all universities and many large higher education providers across the Australian higher education sector; however, its use in many institutions is inconsistent and in some cases biased. The most appropriate, educationally focussed use of text-matching software should adhere to the following parameters:

- Text-matching software should be applied to all text-based assignments, regardless of discipline. It is therefore essential that text-based assignments are submitted electronically to allow for automatic checking by the text-matching software

- The use of text-matching software should not be ‘at the discretion’ of individual faculties, departments or academics;

- All students should be included, not just those suspected of plagiarism or other academic integrity breaches;

- Training should be provided to all staff involved in using text-matching software

- Short, focussed face-to-face workshops should be offered;

- Online support and text-matching software experts should be available for ‘at elbow’ support as needed;

- Regular audits of text-matching ‘similarity reports’ and associated grades should be conducted to ensure that staff are using the reports to address integrity concerns

- Students should have the opportunity to submit their own assignments[9] and correct errors in advance of the submission date

- Regular workshops and online support should be available to assist students in understanding the role of text-matching software and how to use it to improve their academic performance;

- Where appropriate, ‘similarity reports’ should form part of the evidence base for an academic integrity investigation.

It should be noted that text-matching software such as Turnitin or Urkund is less useful for identifying contract cheating than it is for typical plagiarism. However, so-called ‘bespoke’ essays which guarantee that they are ‘plagiarism free’ are often cobbled together bits and pieces from online resources which are able to be identified in a ‘Similarity Report’. Text-matching software therefore remains a useful tool in identifying contract cheating. Research by the CCAD Project (Bretag & Harper et al., 2017) found text-matching reports were the third most common way that staff identified outsourced assignments (after the educator’s knowledge of the student’s academic and linguistic abilities).

Good practice example 19: Foster ‘personalised’ teaching and learning relationships

Research by the CCAD Project (Bretag & Harper et al., 2017) found that students who reported engaging in contract cheating were less satisfied with three aspects of the teaching and learning environment:

- the opportunity to approach teaching staff for assistance

- clarification about assessment requirements, and

- assignment feedback.

These three aspects of a ‘personalised teaching and learning relationship’ can be fostered by:

- clarifying assessment requirements through: task instructions; scaffolding, interactive discussions and assessment or marking rubrics

- being accessible to students for learning help and support, and

- providing constructive, meaningful and timely feedback for each student.

Such a personalised teaching and learning relationship is even more important in light of the finding from the CCAD project mentioned in Good practice example 18 above, that the educator’s knowledge of the student’s academic and linguistic abilities was the key way that contract cheating can be identified.

This focus on establishing positive, interactive learning relationships as part of an overall strategy to promote academic integrity is highlighted by Central Queensland University in numerous forums, as in the following excerpt in Figure 14:

Figure 14: Excerpt from CQ University website – building relationships with students

Source: www.cqu.edu.au/about-us/locations/townsville/townsville

Good practice example 20: Recognise and support the particular needs of International LOTE students (and other ‘at risk’ students)

Research has repeatedly demonstrated that international students who speak a language other than English (LOTE):

- demonstrate less understanding of the meanings and practices of academic integrity (Bretag et al., 2014)

- are twice as likely to have been involved in an academic integrity breach investigation (Bretag et al., 2014), and

- are significantly more likely to report engaging in contract cheating (Bretag & Harper et al., 2017).

This vulnerable group of students is also the most likely to be targeted by unscrupulous commercial cheat sites who offer quick and relatively cheap ‘assistance’ with completing assignments. Struggling with often less than adequate English, confusion about the requirements in the new academic environment, as well as isolation, family pressures and multiple responsibilities, it cannot be surprising that some international LOTE students may be tempted to resort to cheating.

Given that Australian higher education providers actively pursue an internationalisation agenda which includes a strong focus on the recruitment of international students, most of whom speak English as an Additional Language (EAL), it is imperative that higher education providers invest appropriately in support services (language, academic skills, counselling) for this vulnerable group of students. Teaching staff also need appropriate training and support to enable them to meet the needs of this student cohort, while simultaneously upholding academic standards. Central Queensland University makes explicit the importance of adequately supporting international students (see Figure 15).

Figure 15: Excerpt from CQUniversity website – supporting students who need additional assistance

Source: Excerpt from Monitoring Academic Progress – International students, CQUniversity

Other ‘at risk’ students such as first in family, those from low socio-economic backgrounds, educationally ‘less prepared’ (see Bretag et al., 2014), and mature-age students with multiple and competing responsibilities, need to be identified early and appropriately supported through a range of targeted programs.

Good practice example 21: Encourage conversations between staff and students about contract cheating

Contract cheating has repercussions for the credibility of degree programs, the reputations of institutions and long-term consequences for professional practice and the community. However, recent research suggests that non-cheating students are no more concerned about the impact of contract cheating than those students who actually engage in cheating behaviours (Harper & Bretag et al. 2017, in progress). This is shown in Figure 16 below.

Figure 16: Level of ‘concern’ that higher education students are engaging in contract cheating, as reported by teaching staff, cheating students and non-cheating students

Source: Harper & Bretag et al (2017, in progress)

One recommendation to ameliorate this situation is to encourage formal and informal conversations between teachers and students, which raise awareness about the effects of contract cheating. Intrinsically motivated students who would never consider outsourcing their learning to a third party need to be encouraged to speak up when they witness cheating in their own programs or elsewhere on campus. Confidential, simple processes need to be established to facilitate open communication between students and staff so that contract cheating can be identified and appropriately managed.

Good practice example 22: Collaborate across the higher education sector

Contract cheating is not only an institutional, regional, or even national issue. Contract cheating is a concern for all educational providers, right across the globe. A coordinated, collaborative approach is therefore needed, beginning with Australian higher education providers working together to share data and best practices. To date, individual higher education providers in Australia have been reluctant to collaborate, often considering (perhaps naively) that incidents such as MyMaster ‘won’t happen here’. Recent research by the CCAD Project (Bretag & Harper et al., 2017) has demonstrated that no higher education providers are immune, no assignment types can fully ‘design out’ contract cheating, and despite concerted efforts by many institutions and individual educators, a small but concerning percentage of students consider contract cheating to be an appropriate and strategic way to complete their studies. It is therefore imperative that Australian higher education providers collaborate on both small-scale and sector-wide projects to address the threat of contract cheating.

4. Good practices to maintain academic integrity and address contract cheating: Case studies

Case Study 1: Office for Academic Integrity, UniSA Business School

Tracey Bretag, University of South Australia

The Office for Academic Integrity was established in the UniSA Business School in October 2015, partly in response to academic misconduct scandals in the press around essay mills, contract cheating, file sharing, the sale of fake parchments and other egregious academic integrity breaches which had resulted in some universities revoking students’ degrees post-graduation.

An academic integrity working group was convened early in 2015 and provided a number of recommendations relating to contract cheating which ultimately resulted in resources being allocated to establish the Office for Academic Integrity. Working closely with the Dean: Academic, an Advisory Committee and other relevant stakeholders representing the Student Engagement Unit, the Teaching Innovation Unit, UniSA Students Association, the Digital Learning Strategy team and the Marketing Unit, the key objectives of the Office for Academic Integrity are as follows:

- Foster a culture of integrity on campus for both students and staff;

- Provide professional development for teaching staff at all levels in relation to curriculum design, teaching strategies, assessment, marking and implementation of academic integrity policy;

- Build capacity for Curriculum Leaders, Program Directors and Course Coordinators to be champions of academic integrity;

- Encourage students to be active participants in nurturing academic integrity, rather than passive recipients of policy;

- Provide a central point of expertise, support and mentoring for Academic Integrity Officers;

- Ensure consistent and appropriate application of UniSA policy for all academic integrity breaches.

Figure 17: UniSA Business School Office for Academic Integrity promotional material

Source: Office for Academic Integrity marketing material focuses on the positive values and multiple stakeholders of academic integrity

Case Study 2: Academic Integrity Matters Student Organisation, Macquarie University

Sonia Saddiqui, Macquarie University

The Academic Integrity Matters Ambassadors (AIMA) is a student-led organisation founded at Macquarie University in 2014. AIMA was one of the outcomes of the OLT Strategic Priority Project, Academic Integrity in Australia – Understanding and Changing Culture and Practice[10]. AIMA provides a ‘student face’ to academic integrity, which is typically seen by students as a punitive process. Through more meaningful engagement, consultation, collaboration and by enlisting students to serve as change agents in their own right, it is envisaged that students will be able to spread a more positive message about the benefits of academic integrity.

To maximise the viability and long-term potential of the organisation, AIMA enlisted as a chapter of a larger, more well-established organisation – the Academic Integrity Matters student organisation, which is based at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD; founded by Dr Tricia Bertram Gallant in 2009). This affiliation provided AIMA with a ready-made organisational constitution, marketing and branding materials, and other useful resources that enabled the dissemination of a consistent academic integrity message.

Since 2014, AIMA has delivered presentations to students and staff at Macquarie University and at other universities in Sydney and Melbourne, and at a private college in Sydney. The ambassadors have participated in student mentor training, learning skills workshops and lecturer training workshops. They have been featured on television in a Chinese current affairs program, in newspaper, and have been interviewed on local radio. The purpose of the organisation continues to evolve and the outcomes are currently being studied as part of Sonia Saddiqui’s doctoral research (see Figure 18).

Figure 18: Macquarie University Academic Integrity Ambassadors

Source: Students as Partners in Academic Integrity, presentation by Sonia Saddiqui at 7APCEI 2015

Case Study 3: Student Action on Contract Cheating, Deakin University

Wendy Sutherland-Smith and Gavin Hodgkinson, Deakin University

Deakin University has actively engaged with the issue of contract cheating. Policies and processes have been changed to specifically include contract cheating as an area of dishonest conduct and the schedule of outcomes has been changed to ensure students who are proven to have engaged in this conduct face serious consequences. The Deakin University Student Association (DUSA) has been exceptionally active in this space, with ongoing awareness campaigns for all students being undertaken on each of Deakin University campuses.

The DUSA awareness campaigns were initiated following the 2016 International Call for Action Against Contract Cheating to raise awareness across campus and to make students aware that it was not ethical conduct and that there were serious consequences if detected. A most successful part of the campaign was the Deakin University ‘spinning wheel’, which contained a series of ‘outcomes’ from the policy that students could relate to specific scenarios. The advocates introduced students to the spinning wheel, highlighting the idea ‘that there is never an appropriate situation to engage in contract cheating and that doing so is taking a gamble’. DUSA reported that most students were shocked to learn that there were such serious consequences for contract cheating. DUSA also reported that a student was so affected by the DUSA campaign that he went to his lecturer and ‘confessed’ to contract cheating in an assignment as he realised he had made an unethical decision and decided to report his behaviour and seek advice and assistance from DUSA and his lecturer.

DUSA also decided to use the strident red and black colours as these are the colours of the DUSA Dragon, the university mascot and symbol of the various student activity and sporting groups. DUSA plans to extend the range of the contract cheating awareness campaigns in 2017.

Figure 19: Deakin University Contract Cheating Campaign

Source: Photo of contract cheating campaign by Deakin University Students Association

Case Study 4: Good practice in assessment: Innovations to minimise contract cheating

Michael Baird (Curtin University) and Joseph Clare (Murdoch University)

This case study is taken from a large Australian university where a business capstone unit is a final study period unit which every Bachelor of Commerce student must complete in order to graduate. Capstone units are common in business degrees as they pull together previously acquired knowledge, skills and experiential learning, and provide a mechanism to measure students’ abilities before they graduate. Up to the end of 2014 the assessments in the unit were varied and well-rounded, consisting of:

- a business simulation (40% of the unit mark)

- an individual case study (20%)

- a series of weekly eTests (20%), and

- a presentation (20%).

Upon release of the University’s online system for anonymously gathering and reporting student feedback on their learning experiences (eValuate) in mid-2015, it was reported that contract cheating problems were occurring, and at the end of 2015 reports came in from numerous campus locations. At the completion of 2015, the unit was in crisis. Therefore, work was carried out building on a platform provided by criminological theory and crime prevention practice, whereby the assessment elements of the capstone unit were adjusted to reduce the opportunity for contract cheating. The objective for this work was simple: continue to improve the unit and make it harder for students to participate in and get away with contract cheating, but not any harder for students to legitimately learn the material. Some of the interventions included:

- an anonymous feedback facility via a Google Form to allow reporting of issues earlier

- a ‘team shake-up’ which took a member of each team, chosen at random, to switch teams mid-way through the simulation

- increased simulation variability between classes, which means that every class has different simulation market conditions, and

- an academic misconduct information handout (hard copy) distributed to all students and enhanced tutor education with respect to academic misconduct.

One year after implementing these changes, the number of alleged cases of academic misconduct across all assessments in the unit had reduced to 27, down from 183 alleged cases in 2015. This opportunity-reduction success did not hinder any genuine students’ ability to complete the unit and score a high grade, demonstrating that it is possible to minimise contract cheating in a manner consistent with the aim of implementing teaching and supporting learning that influences, motivates, and inspires students to learn.

Reference

Baird, M. & Clare, J. (2017, forthcoming). Removing the opportunity for contract cheating in business capstones: A crime prevention case study, International Journal for Educational Integrity.

Case Study 5: Good practice in assessment: Student-Centred Active Learning Environment with Upside-down Pedagogies (SCALE-UP) to address contract cheating

S. D. Sivasubramaniam, Nottingham Trent University, UK

It is apparent that traditional ‘take-home’ style assessments can create opportunities for students to collude, plagiarise and obtain pre-written essays. In addition, on some occasions there is a disparity between a student’s coursework and their exam performance, with higher grades being attained in the former. Although this disparity may be due to several factors, including poor self-directed learning and revision techniques, inadequate time keeping and exam related stress, etc., some academics suggest that coursework provides opportunities for academic integrity breaches such as contract cheating. To ameliorate this situation, we explored the possibility of using classroom-based active learning and assessment as an alternative to traditional coursework to minimise the opportunities for contract cheating.

The approach was designed to suit a second year biomedical/pharmacology core module with 145 to 174 students at a UK university. In this module, an exercise (which assesses information gathering, self-directed learning and critical analysis skills to enhance students’ revision skills) was transformed from traditional coursework to an in-class SCALE-UP activity. Led by Dr Sivasubramaniam, the peer-assisted activity was split in two 3-hour sessions. In the first session, students were allowed to research a specific topic in groups of four, with sub-topics allocated to each member of the group. Students were allowed to use books, the Internet and any other relevant sources.

This process was assisted by academics giving ‘feed-forward’ leading questions to assist students to critically evaluate their topics. At the end of the session, students uploaded their short notes to the intranet for academic feedback. The second session started with brief academic feedback on students’ short notes, followed by students writing their reports in-class which were then submitted at the end of the session. In this way, the students were: (a) actively researching the topic, (b) involved in peer-assisted learning, (c) directed by discipline academics towards achieving their task goals, and above all, (d) not provided with an opportunity to obtain outside assistance or purchase essays.

Students’ grades in this exercise and in the exam were compared with that of previous years to analyse the impact of this intervention on students’ learning outcomes. Although there were no significant changes for the coursework component, there was a statistically significant increase in students’ exam performance, from a mean of 37% (± STD 17.7) to 58% (±STD 10.1). This suggests that the SCALE-UP methodology not only helped to reduce opportunities for contract cheating but also enhanced students’ learning processes and overall performance.

Case Study 6: Good practice in assessment: Limiting opportunities for students to outsource work to third parties

Ann Rogerson, University of Wollongong

The pressures applied to academics in meeting increasing responsibilities with reduced resources can mean that assessment tasks may be tweaked or recycled from year to year which unintentionally contribute to contract cheating issues. With a little creativity, assessment tasks can be redesigned, not only to limit the potential for students to seek outside paid assistance to complete tasks, but actually engage students in their learning and prepare them for future study tasks and real life responsibilities.

Changes were made to an assessment design in some postgraduate subjects undertaken by international students. Students were introduced to understanding the construction and purpose of annotated bibliographies, extracting key information from journal articles, and integrating a series of annotated bibliographies into a coherent passage via a series of group work tasks. Later tasks developed skills in reflection, linking theory to practical experiences in multi-national groups. Reflective tasks related to in-class discussions or experiences are difficult for others to replicate and where a reflection is purchased, copied or borrowed key elements are usually missing. All the tasks were designed to achieve the learning outcomes, while minimising opportunities to submit plagiarised, borrowed or purchased materials - but in the end this assessment innovation achieved much more than originally anticipated. Reflections from students included their experiences in finally understanding how to read, extract, and use information from journals, recognising the relationship between methodological processes and results and how they had applied these learning experiences to other subjects and thus achieving improved results (see Figure 20).

Figure 20: Assessment Design Poster by Dr Ann Rogerson

Source: Rogerson, A.M. (2015). Designing assessments to develop academic skills while promoting good academic practice and limiting students use of purchased or repurposed materials, Assessment in Higher Education Conference, Birmingham, 16-18 June 2015

Case Study 7: Using text-matching tools to promote learning and reduce plagiarism[11]

Salim Razi, Canakkale Onsekiz Mart University, Turkey

Dr Salim Razi teaches academic writing to English as a Foreign Language (EFL) learners at Canakkale Onsekiz Mart University in Turkey, and for the past five years has used Turnitin to address increasing levels of unoriginal work at the university and promote academic integrity. Following initial success with using Turnitin, which overall saw unoriginal content in students’ work (as shown in Similarity Reports) significantly decrease from 58% to 11%, Dr Razi looked to explore Turnitin’s online feedback tools to develop a systematic approach to providing students with effective digital feedback on their writing via the peer review facility.

One of Dr Razi’s key aims was to encourage those students who are often reluctant to submit their work. His approach uses a combination of self and peer feedback in order to help develop key critical thinking skills which will be essential to students’ future study and work. Students are grouped according to their academic performance; that is, good, moderate and poor and each student receives feedback from each of these groups using a rubric developed by Dr Razi:

Each student receives anonymous feedback from each group, which helps them to develop their writing, whilst also forcing them to look critically at the quality of their own reviews. I require multiple submissions and review these at each stage, which assists my students to revise and develop their critical thinking skills.

Additional feedback is also provided by the tutor who contributes a summative mark. This whole process is facilitated by Turnitin as such a complex approach to offering feedback from multiple sources would be difficult to achieve manually.

Dr Razi has found that by providing students with opportunities to review their own work and the work of peers, students develop their own academic writing style and critical thinking skills. Specifically he has found a positive correlation between students’ academic writing and peer reviewing capabilities, in that better writers give better reviews.

Case Study 8: Processes and training to ensure consistent responses to academic integrity breaches

Greg Preston, University of Newcastle

A Student Academic Conduct Officer (SACO) is an academic staff member appointed to receive reports of alleged academic misconduct and to manage the University of Newcastle’s response to those incidents in line with the Student Academic Integrity Policy. SACOs may be based within a School, across multiple Schools or in another academic unit (such as a campus), and are usually appointed at level C or above, except in certain circumstances.

The training of Student Academic Conduct Officers (SACO’s) involves both initial and ongoing training. Training is facilitated by the SACO Coordinator, who provides strategic oversight of the SACO network with support from the Office of the Deputy Vice Chancellor: Academic.

The initial training includes an orientation session with the SACO coordinator. At this session SACOs are familiarised with University of Newcastle Student Academic Integrity Policy, and introduced to relevant support materials. Those support materials include:

- flowcharts on case handling

- sample letters to communicate with staff and students in terms of investigations and outcomes

- guidelines for penalties, and

- reporting procedures.

The session also includes discussion of a number of scenarios which deal with issues that SACOs are likely to face during their tenure. These scenarios include both procedural and ethical issues.

New SACOs are encouraged to work with the SACO Coordinator when handling their first few cases. Additionally, SACOs are briefed about University of Newcastle initiatives around the Code of Conduct, curriculum and assessment design to reduce plagiarism, and given various tools to help them work with staff in their school or discipline area on minimising academic integrity breaches through these approaches.